Popular Posts

-

Travel To Cairo :ARRIVAL what's the first place in Egypt you will see and spend little time in ? That's Right its' Cairo A...

-

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities , known commonly as the Egyptian Museum or Museum of Cairo , in Cairo, Egypt, is home to an...

-

Staybridge Suites Citystars Cairo Address: Emtedad Makram Obeid Street, Cairo, Egypt price:773 EGP Located in one of the most popu...

-

Ramadan Ramadan calendar month Ramadan is (the ninth month of the Islamic calendar; the month of fasting, the holiest ...

-

Khan El Khalili Khan El Khalili There’s absolutely nothing in Cairo like exploring the enormous shopping labyrinth of Khan...

Blog Archive

- 2013 (5)

-

2010

(49)

- April(1)

-

February(48)

- Pyramids Sound and Light Show

- Pyramids Tour.pictures 3-3

- Pyramids Tour.pictures 2-3

- Pyramids Tour.pictures 1-3

- Pyramids Tour .Cairo

- 2 stars Hotel in Cairo 4-4

- 2 stars Hotel in Cairo 3-4

- 2 stars Hotel in Cairo 2-4

- 2 stars Hotel in Cairo 1-4

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 11-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 10-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 9-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 8-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 7-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 6-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 5-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 4-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 3-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 2-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 1-11

- 4 stars Hotel in Cairo 6-6

- 4 stars Hotel in Cairo 5-6

- 4 stars Hotel in Cairo 4-6

- 4 stars Hotel in Cairo 3-6

- 4 stars Hotel in Cairo 2-6

- 4 stars Hotel in Cairo 1-6

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 10-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 9-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 8-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 7-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 6-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 5-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 4-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 3-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 2-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 1-10

- Travel To Cairo : Transportation

- Travel To Cairo :ARRIVAL

- Everything You need To know About Egypt

- History of ancient Egypt 5-5

- History of ancient Egypt 4-5

- History of ancient Egypt 3-5

- History of ancient Egypt 2-5

- History of ancient Egypt 1-5

- Overview of Egypt 2-2

- Overview of Egypt 1-2

- About Egypt 2-2

- About Egypt 1-2.

My Blog List

FAVORITE Links

Followers

Subscribe via email

AddThis

Tuesday, 9 February 2010

History of ancient Egypt 3-5

New Kingdom

Possibly as a result of the foreign rule of the Hyksos during the Second Intermediate Period, the New Kingdom saw Egypt attempt to create a buffer between the Levant and Egypt, and attain its greatest territorial extent. It expanded far south into Nubia and held wide territories in the Near East. Egyptian armies fought Hittite armies for control of modern-day Syria.

Eighteenth Dynasty

This was a time of great wealth and power for Egypt. Some of the most important and best-known Pharaohs ruled at this time. Hatshepsut was a pharaoh at this time. Hatshepsut is unusual as she was a female pharaoh, a rare occurrence in Egyptian history. She was an ambitious and competent leader, extending Egyptian trade south into present-day Somalia and north into the Mediterranean. She ruled for twenty years through a combination of widespread propaganda and deft political skill. Her co-regent and successor Thutmose III ("the Napoleon of Egypt") expanded Egypt's army and wielded it with great success.

Late in his reign he ordered her name hacked out from her monuments. He fought against Asiatic people and was the most successful of Egyptian pharaohs. Amenhotep III built extensively at the temple of Karnak including the Luxor temple which consisted of two pylons, a colonnade behind the new temple entrance, and a new temple to the goddess Ma'at.

Nineteenth Dynasty

Ramesses I reigned for two years and was succeeded by his son Seti I. Seti I carried on the work of Horemheb in restoring power, control, and respect to Egypt. He also was responsible for creating the temple complex at Abydos.

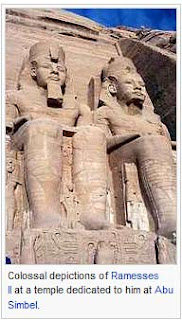

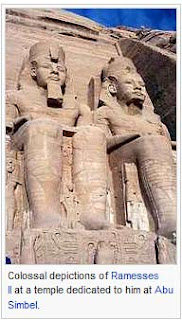

Arguably Ancient Egypt's power as a nation-state peaked during the reign of Ramesses II ("the Great") of the 19th Dynasty. He reigned for 67 years from the age of 18 and carried on his immediate predecessor's work and created many more splendid temples, such as that of Abu Simbel on the Nubian border.

He sought to recover territories in the Levant that had been held by 18th Dynasty Egypt. His campaigns of reconquest culminated in the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC, where he led Egyptian armies against those of the Hittite king Muwatalli II and was caught in history's first recorded military ambush.

Ramesses II was famed for the huge number of children he sired by his various wives and concubines; the tomb he built for his sons (many of whom he outlived) in the Valley of the Kings has proven to be the largest funerary complex in Egypt.

His immediate successors continued the military campaigns, though an increasingly troubled court complicated matters. Ramesses II was succeeded by his son Merneptah and then by Merenptah's son Seti II.

Seti II's throne seems to have been disputed by his half-brother Amenmesse, who may have temporarily ruled from Thebes. Upon his death, Seti II son Siptah, who may have been afflicted with polio during his life, was appointed to the throne by Chancellor Bay, an Asiatic commoner who served as vizier behind the scenes. At Siptah's early death, the throne was assumed by Twosret, the dowager queen of Seti II (and possibly Amenmesses's sister).

A period of anarchy at the end of Twosret's short reign saw a native reaction to foreign control leading to the execution of the chancellor, and placing Setnakhte on the throne, establishing the Twentieth Dynasty.

Twentieth Dynasty

The last "great" pharaoh from the New Kingdom is widely regarded to be Ramesses III, the son of Setnakhte who reigned three decades after the time of Ramesses II.

In Year 8 of his reign, the Sea People, invaded Egypt by land and sea. Ramesses III defeated them in two great land and sea battles. He claimed that he incorporated them as subject people and settled them in Southern Canaan, although there is evidence that they forced their way into Canaan.

Their presence in Canaan may have contributed to the formation of new states in this region such as Philistia after the collapse of the Egyptian Empire. He was also compelled to fight invading Libyan tribesmen in two major campaigns in Egypt's Western Delta in his Year 6 and Year 11 respectively.[15]

The heavy cost of these battles slowly exhausted Egypt's treasury and contributed to the gradual decline of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. The severity of these difficulties is stressed by the fact that the first known labor strike in recorded history occurred during Year 29 of Ramesses III's reign, when the food rations for the Egypt's favoured and elite royal tomb-builders and artisans in the village of Deir el Medina could not be provisioned.[16]

Something in the air prevented much sunlight from reaching the ground and also arrested global tree growth for almost two full decades until 1140 BC.[17] One proposed cause is the Hekla 3 eruption of the Hekla volcano in Iceland, but the dating of that event remains in dispute.

Following Ramesses III's death there was endless bickering between his heirs. Three of his sons would go on to assume power as Ramesses IV, Ramesses VI and Ramesses VIII respectively. However, at this time Egypt was also increasingly beset by a series of droughts, below-normal flooding levels of the Nile, famine, civil unrest and official corruption.

The power of the last pharaoh, Ramesses XI, grew so weak that in the south the High Priests of Amun at Thebes became the effective defacto rulers of Upper Egypt, while Smendes controlled Lower Egypt even before Ramesses XI's death. Smendes would eventually found the Twenty-First dynasty at Tanis.

Third Intermediate Period

After the death of Ramesses XI, his successor Smendes ruled from the city of Tanis in the north, while the High Priests of Amun at Thebes had effective rule of the south of the country, whilst still nominally recognizing Smendes as king.[18] In fact, this division was less significant than it seems, since both priests and pharaohs came from the same family. Piankh, assumed control of Upper Egypt, ruling from Thebes, with the northern limit of his control ending at Al-Hibah.

(The High Priest Herihor had died before Ramesses XI, but also was an all-but-independent ruler in the latter days of the king's reign.) The country was once again split into two parts with the priests in Thebes and the Pharaohs at Tanis.

Their reign seems to be without any other distinction, and they were replaced without any apparent struggle by the Libyan kings of the Twenty-Second Dynasty.

Egypt has long had ties with Libya, and the first king of the new dynasty, Shoshenq I, was a Meshwesh Libyan, who served as the commander of the armies under the last ruler of the Twenty-First Dynasty, Psusennes II.

He unified the country, putting control of the Amun clergy under his own son as the High Priest of Amun, a post that was previously a hereditary appointment.

The scant and patchy nature of the written records from this period suggest that it was unsettled. There appear to have been many subversive groups, which eventually led to the creation of the Twenty-Third Dynasty, which ran concurrent with the latter part of the Twenty-Second Dynasty.

After the withdrawal of Egypt from Nubia at the end of the New Kingdom, a native dynasty took control of Nubia. Under king Piye, the Nubian founder of Twenty-Fifth Dynasty, the Nubians pushed north in an effort to crush his Libyan opponents ruling in the Delta. He managed to attain power as far as Memphis. His opponent Tefnakhte ultimately submitted to him, but he was allowed to remain in power in Lower Egypt and founded the short-lived Twenty-Fourth Dynasty at Sais.

The country was reunited by the Twenty-Second Dynasty founded by Shoshenq I in 945 BC (or 943 BC), who descended from Meshwesh immigrants, originally from Ancient Libya. This brought stability to the country for well over a century. After the reign of Osorkon II the country had again splintered into two states with Shoshenq III of the Twenty-Second Dynasty controlling Lower Egypt by 818 BC while Takelot II and his son (the future Osorkon III) ruled Middle and Upper Egypt.

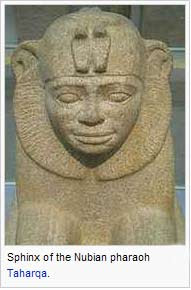

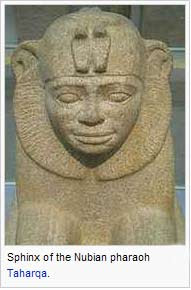

The Nubian kingdom to the south took full advantage of this division and political instability. Piye waged a campaign from Nubia and defeated the combined might of several native-Egyptian rulers such as Peftjaubast, Osorkon IV of Tanis, and Tefnakht of Sais. Piye established the Nubian Twenty-Fifth Dynasty and appointed the defeated rulers to be his provincial governors. He was succeeded first by his brother, Shabaka, and then by his two sons Shebitku and Taharqa.

The international prestige of Egypt declined considerably by this time. The country's international allies had fallen under the sphere of influence of Assyria and from about 700 BC the question became when, not if, there would be war between the two states. Taharqa's reign and that of his successor, Tanutamun, were filled with constant conflict with the Assyrians against whom there were numerous victories, but ultimately Thebes was occupied and Memphis sacked.

Late Period

From 671 BC on, Memphis and the Delta region became the target of many attacks from the Assyrians, who expelled the Nubians and handed over power to client kings of the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty. Psamtik I was the first to be recognized as the king of the whole of Egypt, and he brought increased stability to the country during a 54-year reign from the new capital of Sais. Four successive Saite kings continued guiding Egypt successfully and peacefully from 610-526 BC, keeping the Babylonians away with the help of Greek mercenaries.

By the end of this period a new power was growing in the Near East: Persia. The pharaoh Psamtik III had to face the might of Persia at Pelusium; he was defeated and briefly escaped to Memphis, but ultimately was captured and then executed.

Persian domination

Achaemenid Egypt can be divided into three eras: the first period of Persian occupation when Egypt became a satrapy, followed by an interval of independence, and the second and final period of occupation.

The Persian king Cambyses assumed the formal title of Pharaoh, called himself Mesuti-Re ("Re has given birth"), and sacrificed to the Egyptian gods. He founded the Twenty-seventh dynasty. Egypt was then joined with Cyprus and Phoenicia in the sixth satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire.

Cambyses' successors Darius I the Great and Xerxes pursued a similar policy, visited the country, and warded off an Athenian attack. It is likely that Artaxerxes I and Darius II visited the country as well, although it is not attested in our sources, and did not prevent the Egyptians from feeling unhappy.

During the war of succession after the reign of Darius II, which broke out in 404, they revolted under Amyrtaeus and regained their independence. This sole ruler of the Twenty-eighth dynasty died in 399, and power went to the Twenty-ninth dynasty. The Thirtieth Dynasty was established in 380 BC and lasted until 343 BC. Nectanebo II was the last native king to rule Egypt.

Artaxerxes III (358–338 BC) reconquered the Nile valley for a brief period (343–332 BC). In 332 BC Mazaces handed over the country to Alexander the Great without a fight. The Achaemenid empire had ended, and for a while Egypt was a satrapy in Alexander's empire. Later the Ptolemies and then the Romans successively ruled the Nile valley.

Ptolemaic dynasty

In 332 BC Alexander III of Macedon conquered Egypt with little resistance from the Persians. He was welcomed by the Egyptians as a deliverer. He visited Memphis, and went on pilgrimage to the oracle of Amun at the Oasis of Siwa. The oracle declared him to be the son of Amun.

He conciliated the Egyptians by the respect which he showed for their religion, but he appointed Greeks to virtually all the senior posts in the country, and founded a new Greek city, Alexandria, to be the new capital. The wealth of Egypt could now be harnessed for Alexander's conquest of the rest of the Persian Empire. Early in 331 BC he was ready to depart, and led his forces away to Phoenicia. He left Cleomenes as the ruling nomarch to control Egypt in his absence. Alexander never returned to Egypt.

Following Alexander's death in Babylon in 323 BC, a succession crisis erupted among his generals. Initially, Perdiccas ruled the empire as regent for Alexander's half-brother Arrhidaeus, who became Philip III of Macedon, and then as regent for both Philip III and Alexander's infant son Alexander IV of Macedon, who had not been born at the time of his father's death.

Perdiccas appointed Ptolemy, one of Alexander's closest companions, to be satrap of Egypt. Ptolemy ruled Egypt from 323 BC, nominally in the name of the joint kings Philip III and Alexander IV.

However, as Alexander the Great's empire disintegrated, Ptolemy soon established himself as ruler in his own right. Ptolemy successfully defended Egypt against an invasion by Perdiccas in 321 BC, and consolidated his position in Egypt and the surrounding areas during the Wars of the Diadochi (322 BC-301 BC). In 305 BC, Ptolemy took the title of King. As Ptolemy I Soter ("Saviour"), he founded the Ptolemaic dynasty that was to rule Egypt for nearly 300 years.

The later Ptolemies took on Egyptian traditions by marrying their siblings, had themselves portrayed on public monuments in Egyptian style and dress, and participated in Egyptian religious life.[19][20] Hellenistic culture thrived in Egypt well after the Muslim conquest. The Ptolemies had to fight native rebellions and were involved in foreign and civil wars that led to the decline of the kingdom and its annexation by Rome.

References

15- Nicolas Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt, Blackwell Books, 1992. p.271

16- William F. Edgerton, The Strikes in Ramses III's Twenty-Ninth Year, JNES 10, No. 3 (July 1951), pp. 137-145

17- Frank J. Yurco, "End of the Late Bronze Age and Other Crisis Periods: A Volcanic Cause" in Gold of Praise: Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honor of Edward F. Wente, ed: Emily Teeter & John Larson, (SAOC 58) 1999, pp.456-458

18- Cerny, p.645

19- Bowman (1996) pp25-26

20- Stanwick (2003)

I recommend you that book to read ..See customer reviews below :-

Possibly as a result of the foreign rule of the Hyksos during the Second Intermediate Period, the New Kingdom saw Egypt attempt to create a buffer between the Levant and Egypt, and attain its greatest territorial extent. It expanded far south into Nubia and held wide territories in the Near East. Egyptian armies fought Hittite armies for control of modern-day Syria.

Eighteenth Dynasty

This was a time of great wealth and power for Egypt. Some of the most important and best-known Pharaohs ruled at this time. Hatshepsut was a pharaoh at this time. Hatshepsut is unusual as she was a female pharaoh, a rare occurrence in Egyptian history. She was an ambitious and competent leader, extending Egyptian trade south into present-day Somalia and north into the Mediterranean. She ruled for twenty years through a combination of widespread propaganda and deft political skill. Her co-regent and successor Thutmose III ("the Napoleon of Egypt") expanded Egypt's army and wielded it with great success.

Late in his reign he ordered her name hacked out from her monuments. He fought against Asiatic people and was the most successful of Egyptian pharaohs. Amenhotep III built extensively at the temple of Karnak including the Luxor temple which consisted of two pylons, a colonnade behind the new temple entrance, and a new temple to the goddess Ma'at.

Nineteenth Dynasty

Ramesses I reigned for two years and was succeeded by his son Seti I. Seti I carried on the work of Horemheb in restoring power, control, and respect to Egypt. He also was responsible for creating the temple complex at Abydos.

Arguably Ancient Egypt's power as a nation-state peaked during the reign of Ramesses II ("the Great") of the 19th Dynasty. He reigned for 67 years from the age of 18 and carried on his immediate predecessor's work and created many more splendid temples, such as that of Abu Simbel on the Nubian border.

He sought to recover territories in the Levant that had been held by 18th Dynasty Egypt. His campaigns of reconquest culminated in the Battle of Kadesh in 1274 BC, where he led Egyptian armies against those of the Hittite king Muwatalli II and was caught in history's first recorded military ambush.

Ramesses II was famed for the huge number of children he sired by his various wives and concubines; the tomb he built for his sons (many of whom he outlived) in the Valley of the Kings has proven to be the largest funerary complex in Egypt.

His immediate successors continued the military campaigns, though an increasingly troubled court complicated matters. Ramesses II was succeeded by his son Merneptah and then by Merenptah's son Seti II.

Seti II's throne seems to have been disputed by his half-brother Amenmesse, who may have temporarily ruled from Thebes. Upon his death, Seti II son Siptah, who may have been afflicted with polio during his life, was appointed to the throne by Chancellor Bay, an Asiatic commoner who served as vizier behind the scenes. At Siptah's early death, the throne was assumed by Twosret, the dowager queen of Seti II (and possibly Amenmesses's sister).

A period of anarchy at the end of Twosret's short reign saw a native reaction to foreign control leading to the execution of the chancellor, and placing Setnakhte on the throne, establishing the Twentieth Dynasty.

Twentieth Dynasty

The last "great" pharaoh from the New Kingdom is widely regarded to be Ramesses III, the son of Setnakhte who reigned three decades after the time of Ramesses II.

In Year 8 of his reign, the Sea People, invaded Egypt by land and sea. Ramesses III defeated them in two great land and sea battles. He claimed that he incorporated them as subject people and settled them in Southern Canaan, although there is evidence that they forced their way into Canaan.

Their presence in Canaan may have contributed to the formation of new states in this region such as Philistia after the collapse of the Egyptian Empire. He was also compelled to fight invading Libyan tribesmen in two major campaigns in Egypt's Western Delta in his Year 6 and Year 11 respectively.[15]

The heavy cost of these battles slowly exhausted Egypt's treasury and contributed to the gradual decline of the Egyptian Empire in Asia. The severity of these difficulties is stressed by the fact that the first known labor strike in recorded history occurred during Year 29 of Ramesses III's reign, when the food rations for the Egypt's favoured and elite royal tomb-builders and artisans in the village of Deir el Medina could not be provisioned.[16]

Something in the air prevented much sunlight from reaching the ground and also arrested global tree growth for almost two full decades until 1140 BC.[17] One proposed cause is the Hekla 3 eruption of the Hekla volcano in Iceland, but the dating of that event remains in dispute.

Following Ramesses III's death there was endless bickering between his heirs. Three of his sons would go on to assume power as Ramesses IV, Ramesses VI and Ramesses VIII respectively. However, at this time Egypt was also increasingly beset by a series of droughts, below-normal flooding levels of the Nile, famine, civil unrest and official corruption.

The power of the last pharaoh, Ramesses XI, grew so weak that in the south the High Priests of Amun at Thebes became the effective defacto rulers of Upper Egypt, while Smendes controlled Lower Egypt even before Ramesses XI's death. Smendes would eventually found the Twenty-First dynasty at Tanis.

Third Intermediate Period

After the death of Ramesses XI, his successor Smendes ruled from the city of Tanis in the north, while the High Priests of Amun at Thebes had effective rule of the south of the country, whilst still nominally recognizing Smendes as king.[18] In fact, this division was less significant than it seems, since both priests and pharaohs came from the same family. Piankh, assumed control of Upper Egypt, ruling from Thebes, with the northern limit of his control ending at Al-Hibah.

(The High Priest Herihor had died before Ramesses XI, but also was an all-but-independent ruler in the latter days of the king's reign.) The country was once again split into two parts with the priests in Thebes and the Pharaohs at Tanis.

Their reign seems to be without any other distinction, and they were replaced without any apparent struggle by the Libyan kings of the Twenty-Second Dynasty.

Egypt has long had ties with Libya, and the first king of the new dynasty, Shoshenq I, was a Meshwesh Libyan, who served as the commander of the armies under the last ruler of the Twenty-First Dynasty, Psusennes II.

He unified the country, putting control of the Amun clergy under his own son as the High Priest of Amun, a post that was previously a hereditary appointment.

The scant and patchy nature of the written records from this period suggest that it was unsettled. There appear to have been many subversive groups, which eventually led to the creation of the Twenty-Third Dynasty, which ran concurrent with the latter part of the Twenty-Second Dynasty.

After the withdrawal of Egypt from Nubia at the end of the New Kingdom, a native dynasty took control of Nubia. Under king Piye, the Nubian founder of Twenty-Fifth Dynasty, the Nubians pushed north in an effort to crush his Libyan opponents ruling in the Delta. He managed to attain power as far as Memphis. His opponent Tefnakhte ultimately submitted to him, but he was allowed to remain in power in Lower Egypt and founded the short-lived Twenty-Fourth Dynasty at Sais.

The country was reunited by the Twenty-Second Dynasty founded by Shoshenq I in 945 BC (or 943 BC), who descended from Meshwesh immigrants, originally from Ancient Libya. This brought stability to the country for well over a century. After the reign of Osorkon II the country had again splintered into two states with Shoshenq III of the Twenty-Second Dynasty controlling Lower Egypt by 818 BC while Takelot II and his son (the future Osorkon III) ruled Middle and Upper Egypt.

The Nubian kingdom to the south took full advantage of this division and political instability. Piye waged a campaign from Nubia and defeated the combined might of several native-Egyptian rulers such as Peftjaubast, Osorkon IV of Tanis, and Tefnakht of Sais. Piye established the Nubian Twenty-Fifth Dynasty and appointed the defeated rulers to be his provincial governors. He was succeeded first by his brother, Shabaka, and then by his two sons Shebitku and Taharqa.

The international prestige of Egypt declined considerably by this time. The country's international allies had fallen under the sphere of influence of Assyria and from about 700 BC the question became when, not if, there would be war between the two states. Taharqa's reign and that of his successor, Tanutamun, were filled with constant conflict with the Assyrians against whom there were numerous victories, but ultimately Thebes was occupied and Memphis sacked.

Late Period

From 671 BC on, Memphis and the Delta region became the target of many attacks from the Assyrians, who expelled the Nubians and handed over power to client kings of the Twenty-Sixth Dynasty. Psamtik I was the first to be recognized as the king of the whole of Egypt, and he brought increased stability to the country during a 54-year reign from the new capital of Sais. Four successive Saite kings continued guiding Egypt successfully and peacefully from 610-526 BC, keeping the Babylonians away with the help of Greek mercenaries.

By the end of this period a new power was growing in the Near East: Persia. The pharaoh Psamtik III had to face the might of Persia at Pelusium; he was defeated and briefly escaped to Memphis, but ultimately was captured and then executed.

Persian domination

Achaemenid Egypt can be divided into three eras: the first period of Persian occupation when Egypt became a satrapy, followed by an interval of independence, and the second and final period of occupation.

The Persian king Cambyses assumed the formal title of Pharaoh, called himself Mesuti-Re ("Re has given birth"), and sacrificed to the Egyptian gods. He founded the Twenty-seventh dynasty. Egypt was then joined with Cyprus and Phoenicia in the sixth satrapy of the Achaemenid Empire.

Cambyses' successors Darius I the Great and Xerxes pursued a similar policy, visited the country, and warded off an Athenian attack. It is likely that Artaxerxes I and Darius II visited the country as well, although it is not attested in our sources, and did not prevent the Egyptians from feeling unhappy.

During the war of succession after the reign of Darius II, which broke out in 404, they revolted under Amyrtaeus and regained their independence. This sole ruler of the Twenty-eighth dynasty died in 399, and power went to the Twenty-ninth dynasty. The Thirtieth Dynasty was established in 380 BC and lasted until 343 BC. Nectanebo II was the last native king to rule Egypt.

Artaxerxes III (358–338 BC) reconquered the Nile valley for a brief period (343–332 BC). In 332 BC Mazaces handed over the country to Alexander the Great without a fight. The Achaemenid empire had ended, and for a while Egypt was a satrapy in Alexander's empire. Later the Ptolemies and then the Romans successively ruled the Nile valley.

Ptolemaic dynasty

In 332 BC Alexander III of Macedon conquered Egypt with little resistance from the Persians. He was welcomed by the Egyptians as a deliverer. He visited Memphis, and went on pilgrimage to the oracle of Amun at the Oasis of Siwa. The oracle declared him to be the son of Amun.

He conciliated the Egyptians by the respect which he showed for their religion, but he appointed Greeks to virtually all the senior posts in the country, and founded a new Greek city, Alexandria, to be the new capital. The wealth of Egypt could now be harnessed for Alexander's conquest of the rest of the Persian Empire. Early in 331 BC he was ready to depart, and led his forces away to Phoenicia. He left Cleomenes as the ruling nomarch to control Egypt in his absence. Alexander never returned to Egypt.

Following Alexander's death in Babylon in 323 BC, a succession crisis erupted among his generals. Initially, Perdiccas ruled the empire as regent for Alexander's half-brother Arrhidaeus, who became Philip III of Macedon, and then as regent for both Philip III and Alexander's infant son Alexander IV of Macedon, who had not been born at the time of his father's death.

Perdiccas appointed Ptolemy, one of Alexander's closest companions, to be satrap of Egypt. Ptolemy ruled Egypt from 323 BC, nominally in the name of the joint kings Philip III and Alexander IV.

However, as Alexander the Great's empire disintegrated, Ptolemy soon established himself as ruler in his own right. Ptolemy successfully defended Egypt against an invasion by Perdiccas in 321 BC, and consolidated his position in Egypt and the surrounding areas during the Wars of the Diadochi (322 BC-301 BC). In 305 BC, Ptolemy took the title of King. As Ptolemy I Soter ("Saviour"), he founded the Ptolemaic dynasty that was to rule Egypt for nearly 300 years.

The later Ptolemies took on Egyptian traditions by marrying their siblings, had themselves portrayed on public monuments in Egyptian style and dress, and participated in Egyptian religious life.[19][20] Hellenistic culture thrived in Egypt well after the Muslim conquest. The Ptolemies had to fight native rebellions and were involved in foreign and civil wars that led to the decline of the kingdom and its annexation by Rome.

References

15- Nicolas Grimal, A History of Ancient Egypt, Blackwell Books, 1992. p.271

16- William F. Edgerton, The Strikes in Ramses III's Twenty-Ninth Year, JNES 10, No. 3 (July 1951), pp. 137-145

17- Frank J. Yurco, "End of the Late Bronze Age and Other Crisis Periods: A Volcanic Cause" in Gold of Praise: Studies on Ancient Egypt in Honor of Edward F. Wente, ed: Emily Teeter & John Larson, (SAOC 58) 1999, pp.456-458

18- Cerny, p.645

19- Bowman (1996) pp25-26

20- Stanwick (2003)

I recommend you that book to read ..See customer reviews below :-

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment