Popular Posts

-

Travel To Cairo :ARRIVAL what's the first place in Egypt you will see and spend little time in ? That's Right its' Cairo A...

-

The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities , known commonly as the Egyptian Museum or Museum of Cairo , in Cairo, Egypt, is home to an...

-

Staybridge Suites Citystars Cairo Address: Emtedad Makram Obeid Street, Cairo, Egypt price:773 EGP Located in one of the most popu...

-

Ramadan Ramadan calendar month Ramadan is (the ninth month of the Islamic calendar; the month of fasting, the holiest ...

-

Khan El Khalili Khan El Khalili There’s absolutely nothing in Cairo like exploring the enormous shopping labyrinth of Khan...

Blog Archive

- 2013 (5)

-

2010

(49)

- April(1)

-

February(48)

- Pyramids Sound and Light Show

- Pyramids Tour.pictures 3-3

- Pyramids Tour.pictures 2-3

- Pyramids Tour.pictures 1-3

- Pyramids Tour .Cairo

- 2 stars Hotel in Cairo 4-4

- 2 stars Hotel in Cairo 3-4

- 2 stars Hotel in Cairo 2-4

- 2 stars Hotel in Cairo 1-4

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 11-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 10-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 9-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 8-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 7-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 6-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 5-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 4-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 3-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 2-11

- 3 stars Hotel in Cairo 1-11

- 4 stars Hotel in Cairo 6-6

- 4 stars Hotel in Cairo 5-6

- 4 stars Hotel in Cairo 4-6

- 4 stars Hotel in Cairo 3-6

- 4 stars Hotel in Cairo 2-6

- 4 stars Hotel in Cairo 1-6

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 10-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 9-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 8-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 7-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 6-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 5-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 4-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 3-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 2-10

- 5 stars Hotel in Cairo 1-10

- Travel To Cairo : Transportation

- Travel To Cairo :ARRIVAL

- Everything You need To know About Egypt

- History of ancient Egypt 5-5

- History of ancient Egypt 4-5

- History of ancient Egypt 3-5

- History of ancient Egypt 2-5

- History of ancient Egypt 1-5

- Overview of Egypt 2-2

- Overview of Egypt 1-2

- About Egypt 2-2

- About Egypt 1-2.

My Blog List

FAVORITE Links

Followers

Subscribe via email

AddThis

Friday, 12 February 2010

History of ancient Egypt 5-5

Language

The Egyptian language is a northern Afro-Asiatic language closely related to the Berber and Semitic languages.[1] It has the longest history of any language, having been written from c. 3200 BC to the Middle Ages and remaining as a spoken language for longer. The phases of Ancient Egyptian are Old Egyptian, Middle Egyptian (Classical Egyptian), Late Egyptian, Demotic and Coptic.[2] Egyptian writings do not show dialect differences before Coptic, but it was probably spoken in regional dialects around Memphis and later Thebes.[3]

Ancient Egyptian was a synthetic language, but it became more analytic later on. Late Egyptian develops prefixal definite and indefinite articles, which replace the older inflectional suffixes. There is a change from the older Verb Subject Object word order to Subject Verb Object.[4] The Egyptian hieroglyphic, hieratic, and demotic scripts were eventually replaced by the more phonetic Coptic alphabet. Coptic is still used in the liturgy of the Egyptian Orthodox Church, and traces of it are found in modern Egyptian Arabic.[5]

Sounds and grammar

Ancient Egyptian has 25 consonants similar to those of other Afro-Asiatic languages. These include pharyngeal and emphatic consonants, voiced and voiceless stops, voiceless fricatives and voiced and voiceless affricates. It has three long and three short vowels, which expanded in Later Egyptian to about nine.[6] The basic word in Egyptian, similar to Semitic and Berber, is a triliteral or biliteral root of consonants and semiconsonants. Suffixes are added to form words. The verb conjugation corresponds to the person. For example, the triconsonantal skeleton S-Ḏ-M is the semantic core of the word 'hear'; its basic conjugation is sḏm=f 'he hears'. If the subject is a noun, suffixes are not added to the verb:[7] sḏm ḥmt 'the woman hears'.

Adjectives are derived from nouns through a process that Egyptologists call nisbation because of its similarity with Arabic.[8] The word order is PREDICATE-SUBJECT in verbal and adjectival sentences, and SUBJECT-PREDICATE in nominal and adverbial sentences.[9] The subject can be moved to the beginning of sentences if it is long and is followed by a resumptive pronoun.[10] Verbs and nouns are negated by the particle n, but nn is used for adverbial and adjectival sentences. Stress falls on the ultimate or penultimate syllable, which can be open (CV) or closed (CVC).[11]

Writing

Hieroglyphic writing dates to c. 3200 BC, and is composed of some 500 symbols. A hieroglyph can represent a word, a sound, or a silent determinative; and the same symbol can serve different purposes in different contexts. Hieroglyphs were a formal script, used on stone monuments and in tombs, that could be as detailed as individual works of art. In day-to-day writing, scribes used a cursive form of writing, called hieratic, which was quicker and easier. While formal hieroglyphs may be read in rows or columns in either direction (though typically written from right to left), hieratic was always written from right to left, usually in horizontal rows. A new form of writing, Demotic, became the prevalent writing style, and it is this form of writing — along with formal hieroglyphs — that accompany the Greek text on the Rosetta Stone.[citation needed]

Around the 1st century AD, the Coptic alphabet started to be used alongside the Demotic script. Coptic is a modified Greek alphabet with the addition of some Demotic signs.[13] Although formal hieroglyphs were used in a ceremonial role until the 4th century AD, towards the end only a small handful of priests could still read them. As the traditional religious establishments were disbanded, knowledge of hieroglyphic writing was mostly lost. Attempts to decipher them date to the Byzantine[14] and Islamic periods in Egypt,[15] but only in 822, after the discovery of the Rosetta stone and years of research by Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion, were hieroglyphs almost fully deciphered.[16]

Literature

Writing first appeared in association with kingship on labels and tags for items found in royal tombs. It was primarily an occupation of the scribes, who worked out of the Per Ankh institution or the House of Life. The latter comprised offices, libraries (called House of Books), laboratories and observatories.[17] Some of the best-known pieces of ancient Egyptian literature, such as the Pyramid and Coffin Texts, were written in Classical Egyptian, which continued to be the language of writing until about 300 BC. Later Egyptian was spoken from the New Kingdom onward and is represented in Ramesside administrative documents, love poetry and tales, as well as in Demotic and Coptic texts. During this period, the tradition of writing had evolved into the tomb autobiography, such as those of Harkhuf and Weni. The genre known as Sebayt (Instructions) was developed to communicate teachings and guidance from famous nobles; the Ipuwer papyrus, a poem of lamentations describing natural disasters and social upheaval, is a famous example.

The Story of Sinuhe, written in Middle Egyptian, might be the classic of Egyptian literature.[18] Also written at this time was the Westcar Papyrus, a set of stories told to Khufu by his sons relating the marvels performed by priests.[19] The Instruction of Amenemope is considered a masterpiece of near-eastern literature.[20] Towards the end of the New Kingdom, the vernacular language was more often employed to write popular pieces like the Story of Wenamun and the Instruction of Any. The former tells the story of a noble who is robbed on his way to buy cedar from Lebanon and of his struggle to return to Egypt. From about 700 BC, narrative stories and instructions, such as the popular Instructions of Onchsheshonqy, as well as personal and business documents were written in the demotic script and phase of Egyptian. Many stories written in demotic during the Graeco-Roman period were set in previous historical eras, when Egypt was an independent nation ruled by great pharaohs such as Ramesses II.[21]

Culture

Daily life

Most ancient Egyptians were farmers tied to the land. Their dwellings were restricted to immediate family members, and were constructed of mud-brick designed to remain cool in the heat of the day. Each home had a kitchen with an open roof, which contained a grindstone for milling flour and a small oven for baking bread.[22] Walls were painted white and could be covered with dyed linen wall hangings. Floors were covered with reed mats, while wooden stools, beds raised from the floor and individual tables comprised the furniture.[23]

The ancient Egyptians placed a great value on hygiene and appearance. Most bathed in the Nile and used a pasty soap made from animal fat and chalk. Men shaved their entire bodies for cleanliness, and aromatic perfumes and ointments covered bad odors and soothed skin.[24] Clothing was made from simple linen sheets that were bleached white, and both men and women of the upper classes wore wigs, jewelry, and cosmetics. Children went without clothing until maturity, at about age 12, and at this age males were circumcised and had their heads shaved. Mothers were responsible for taking care of the children, while the father provided the family's income.[25]

The staple diet consisted of bread and beer, supplemented with vegetables such as onions and garlic, and fruit such as dates and figs. Wine and meat were enjoyed by all on feast days while the upper classes indulged on a more regular basis. Fish, meat, and fowl could be salted or dried, and could be cooked in stews or roasted on a grill.[26] Music and dance were popular entertainments for those who could afford them. Early instruments included flutes and harps, while instruments similar to trumpets, oboes, and pipes developed later and became popular. In the New Kingdom, the Egyptians played on bells, cymbals, tambourines, and drums and imported lutes and lyres from Asia.[27] The sistrum was a rattle-like musical instrument that was especially important in religious ceremonies.

The ancient Egyptians enjoyed a variety of leisure activities, including games and music. Senet, a board game where pieces moved according to random chance, was particularly popular from the earliest times; another similar game was mehen, which had a circular gaming board. Juggling and ball games were popular with children, and wrestling is also documented in a tomb at Beni Hasan.[28] The wealthy members of ancient Egyptian society enjoyed hunting and boating as well.

The excavation of the workers village of Deir el-Madinah has resulted in one of the most thoroughly documented accounts of community life in the ancient world that spans almost four hundred years. There is no comparable site in which the organisation, social interactions, working and living conditions of a community can be studied in such detail.[29]

Architecture

The architecture of ancient Egypt includes some of the most famous structures in the world: the Great Pyramids of Giza and the temples at Thebes. Building projects were organized and funded by the state for religious and commemorative purposes, but also to reinforce the power of the pharaoh. The ancient Egyptians were skilled builders; using simple but effective tools and sighting instruments, architects could build large stone structures with accuracy and precision.[30]

The domestic dwellings of elite and ordinary Egyptians alike were constructed from perishable materials such as mud bricks and wood, and have not survived. Peasants lived in simple homes, while the palaces of the elite were more elaborate structures. A few surviving New Kingdom palaces, such as those in Malkata and Amarna, show richly decorated walls and floors with scenes of people, birds, water pools, deities and geometric designs.[31] Important structures such as temples and tombs that were intended to last forever were constructed of stone instead of bricks. The architectural elements used in the world's first large-scale stone building, Djoser's mortuary complex, include post and lintel supports in the papyrus and lotus motif.

The earliest preserved ancient Egyptian temples, such as those at Giza, consist of single, enclosed halls with roof slabs supported by columns. In the New Kingdom, architects added the pylon, the open courtyard, and the enclosed hypostyle hall to the front of the temple's sanctuary, a style that was standard until the Graeco-Roman period.[32] The earliest and most popular tomb architecture in the Old Kingdom was the mastaba, a flat-roofed rectangular structure of mudbrick or stone built over an underground burial chamber. The step pyramid of Djoser is a series of stone mastabas stacked on top of each other. Pyramids were built during the Old and Middle Kingdoms, but later rulers abandoned them in favor of less conspicuous rock-cut tombs.[33]

Art

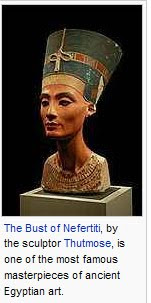

The ancient Egyptians produced art to serve functional purposes. For over 3500 years, artists adhered to artistic forms and iconography that were developed during the Old Kingdom, following a strict set of principles that resisted foreign influence and internal change.[34] These artistic standards — simple lines, shapes, and flat areas of color combined with the characteristic flat projection of figures with no indication of spatial depth — created a sense of order and balance within a composition. Images and text were intimately interwoven on tomb and temple walls, coffins, stelae, and even statues. The Narmer Palette, for example, displays figures which may also be read as hieroglyphs.[35] Because of the rigid rules that governed its highly stylized and symbolic appearance, ancient Egyptian art served its political and religious purposes with precision and clarity.[36]

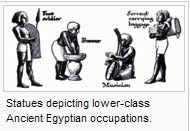

Ancient Egyptian artisans used stone to carve statues and fine reliefs, but used wood as a cheap and easily carved substitute. Paints were obtained from minerals such as iron ores (red and yellow ochres), copper ores (blue and green), soot or charcoal (black), and limestone (white). Paints could be mixed with gum arabic as a binder and pressed into cakes, which could be moistened with water when needed.[37] Pharaohs used reliefs to record victories in battle, royal decrees, and religious scenes. Common citizens had access to pieces of funerary art, such as shabti statues and books of the dead, which they believed would protect them in the afterlife.[38] During the Middle Kingdom, wooden or clay models depicting scenes from everyday life became popular additions to the tomb. In an attempt to duplicate the activities of the living in the afterlife, these models show laborers, houses, boats, and even military formations that are scale representations of the ideal ancient Egyptian afterlife.[39]

Despite the homogeneity of ancient Egyptian art, the styles of particular times and places sometimes reflected changing cultural or political attitudes. After the invasion of the Hyksos in the Second Intermediate Period, Minoan-style frescoes were found in Avaris.[40] The most striking example of a politically driven change in artistic forms comes from the Amarna period, where figures were radically altered to conform to Akhenaten's revolutionary religious ideas.[41] This style, known as Amarna art, was quickly and thoroughly erased after Akhenaten's death and replaced by the traditional forms.[42]

Religious beliefs

Beliefs in the divine and in the afterlife were ingrained in ancient Egyptian civilization from its inception; pharaonic rule was based on the divine right of kings. The Egyptian pantheon was populated by gods who had supernatural powers and were called on for help or protection. However, the gods were not always viewed as benevolent, and Egyptians believed they had to be appeased with offerings and prayers. The structure of this pantheon changed continually as new deities were promoted in the hierarchy, but priests made no effort to organize the diverse and sometimes conflicting creation myths and stories into a coherent system.[43] These various conceptions of divinity were not considered contradictory but rather layers in the multiple facets of reality.[44]

Gods were worshiped in cult temples administered by priests acting on the king's behalf. At the center of the temple was the cult statue in a shrine. Temples were not places of public worship or congregation, and only on select feast days and celebrations was a shrine carrying the statue of the god brought out for public worship. Normally, the god's domain was sealed off from the outside world and was only accessible to temple officials. Common citizens could worship private statues in their homes, and amulets offered protection against the forces of chaos.[45] After the New Kingdom, the pharaoh's role as a spiritual intermediary was de-emphasized as religious customs shifted to direct worship of the gods. As a result, priests developed a system of oracles to communicate the will of the gods directly to the people.[46]

The Egyptians believed that every human being was composed of physical and spiritual parts or aspects. In addition to the body, each person had a šwt (shadow), a ba (personality or soul), a ka (life-force), and a name.[47] The heart, rather than the brain, was considered the seat of thoughts and emotions. After death, the spiritual aspects were released from the body and could move at will, but they required the physical remains (or a substitute, such as a statue) as a permanent home. The ultimate goal of the deceased was to rejoin his ka and ba and become one of the "blessed dead", living on as an akh, or "effective one". In order for this to happen, the deceased had to be judged worthy in a trial, in which the heart was weighed against a "feather of truth". If deemed worthy, the deceased could continue their existence on earth in spiritual form.[48]

Burial customs

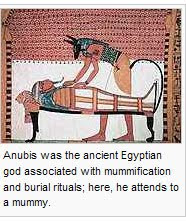

The ancient Egyptians maintained an elaborate set of burial customs that they believed were necessary to ensure immortality after death. These customs involved preserving the body by mummification, performing burial ceremonies, and interring, along with the body, goods to be used by the deceased in the afterlife.[38] Before the Old Kingdom, bodies buried in desert pits were naturally preserved by desiccation. The arid, desert conditions continued to be a boon throughout the history of ancient Egypt for the burials of the poor, who could not afford the elaborate burial preparations available to the elite. Wealthier Egyptians began to bury their dead in stone tombs and, as a result, they made use of artificial mummification, which involved removing the internal organs, wrapping the body in linen, and burying it in a rectangular stone sarcophagus or wooden coffin. Beginning in the Fourth Dynasty, some parts were preserved separately in canopic jars.[49]

By the New Kingdom, the ancient Egyptians had perfected the art of mummification; the best technique took 70 days and involved removing the internal organs, removing the brain through the nose, and desiccating the body in a mixture of salts called natron. The body was then wrapped in linen with protective amulets inserted between layers and placed in a decorated anthropoid coffin. Mummies of the Late Period were also placed in painted cartonnage mummy cases. Actual preservation practices declined during the Ptolemaic and Roman eras, while greater emphasis was placed on the outer appearance of the mummy, which was decorated.[50]

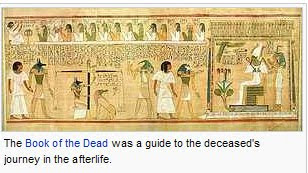

Wealthy Egyptians were buried with larger quantities of luxury items, but all burials, regardless of social status, included goods for the deceased. Beginning in the New Kingdom, books of the dead were included in the grave, along with shabti statues that were believed to perform manual labor for them in the afterlife.[51] Rituals in which the deceased was magically re-animated accompanied burials. After burial, living relatives were expected to occasionally bring food to the tomb and recite prayers on behalf of the deceased.[52]

Military

The ancient Egyptian military was responsible for defending Egypt against foreign invasion, and for maintaining Egypt's domination in the ancient Near East. The military protected mining expeditions to the Sinai during the Old Kingdom and fought civil wars during the First and Second Intermediate Periods. The military was responsible for maintaining fortifications along important trade routes, such as those found at the city of Buhen on the way to Nubia. Forts also were constructed to serve as military bases, such as the fortress at Sile, which was a base of operations for expeditions to the Levant. In the New Kingdom, a series of pharaohs used the standing Egyptian army to attack and conquer Kush and parts of the Levant.[53]

Typical military equipment included bows and arrows, spears, and round-topped shields made by stretching animal skin over a wooden frame. In the New Kingdom, the military began using chariots that had earlier been introduced by the Hyksos invaders. Weapons and armor continued to improve after the adoption of bronze: shields were now made from solid wood with a bronze buckle, spears were tipped with a bronze point, and the Khopesh was adopted from Asiatic soldiers.[54] The pharaoh was usually depicted in art and literature riding at the head of the army, and there is evidence that at least a few pharaohs, such as Seqenenre Tao II and his sons, did do so.[55] Soldiers were recruited from the general population, but during, and especially after, the New Kingdom, mercenaries from Nubia, Kush, and Libya were hired to fight for Egypt.[56]

Technology, medicine, and mathematics

Technology

In technology, medicine and mathematics, ancient Egypt achieved a relatively high standard of productivity and sophistication. Traditional empiricism, as evidenced by the Edwin Smith and Ebers papyri (c. 600 BC), is first credited to Egypt, and the roots of the scientific method can also be traced back to the ancient Egyptians.[citation needed] The Egyptians created their own alphabet and decimal system.

Faience and glass

Even before the Old Kingdom, the ancient Egyptians had developed a glassy material known as faience, which they treated as a type of artificial semi-precious stone. Faience is a non-clay ceramic made of silica, small amounts of lime and soda, and a colorant, typically copper.[57] The material was used to make beads, tiles, figurines, and small wares. Several methods can be used to create faience, but typically production involved application of the powdered materials in the form of a paste over a clay core, which was then fired. By a related technique, the ancient Egyptians produced a pigment known as Egyptian Blue, also called blue frit, which is produced by fusing (or sintering) silica, copper, lime, and an alkali such as natron. The product can be ground up and used as a pigment.[58]

The ancient Egyptians could fabricate a wide variety of objects from glass with great skill, but it is not clear whether they developed the process independently.[59] It is also unclear whether they made their own raw glass or merely imported pre-made ingots, which they melted and finished. However, they did have technical expertise in making objects, as well as adding trace elements to control the color of the finished glass. A range of colors could be produced, including yellow, red, green, blue, purple, and white, and the glass could be made either transparent or opaque.[60]

Medicine

The medical problems of the ancient Egyptians stemmed directly from their environment. Living and working close to the Nile brought hazards from malaria and debilitating schistosomiasis parasites, which caused liver and intestinal damage. Dangerous wildlife such as crocodiles and hippos were also a common threat. The life-long labors of farming and building put stress on the spine and joints, and traumatic injuries from construction and warfare all took a significant toll on the body. The grit and sand from stone-ground flour abraded teeth, leaving them susceptible to abscesses (though caries were rare).[61]

The diets of the wealthy were rich in sugars, which promoted periodontal disease.[62] Despite the flattering physiques portrayed on tomb walls, the overweight mummies of many of the upper class show the effects of a life of overindulgence.[63] Adult life expectancy was about 35 for men and 30 for women, but reaching adulthood was difficult as about one-third of the population died in infancy.[64]

Ancient Egyptian physicians were renowned in the ancient Near East for their healing skills, and some, like Imhotep, remained famous long after their deaths.[65] Herodotus remarked that there was a high degree of specialization among Egyptian physicians, with some treating only the head or the stomach, while others were eye-doctors and dentists.[66] Training of physicians took place at the Per Ankh or "House of Life" institution, most notably those headquartered in Per-Bastet during the New Kingdom and at Abydos and Saïs in the Late period. Medical papyri show empirical knowledge of anatomy, injuries, and practical treatments.[67]

Wounds were treated by bandaging with raw meat, white linen, sutures, nets, pads and swabs soaked with honey to prevent infection,[68] while opium was used to relieve pain. Garlic and onions were used regularly to promote good health and were thought to relieve asthma symptoms. Ancient Egyptian surgeons stitched wounds, set broken bones, and amputated diseased limbs, but they recognized that some injuries were so serious that they could only make the patient comfortable until he died.[69]

Shipbuilding

Early Egyptians knew how to assemble planks of wood into a ship hull as early as 3000 BC. The Archaeological Institute of America reports[6] that the oldest ships yet unearthed, a group of 14 discovered in Abydos, were constructed of wooden planks which were "sewn" together. Discovered by Egyptologist David O'Connor of New York University,[70] woven straps were found to have been used to lash the planks together,[6] and reeds or grass stuffed between the planks helped to seal the seams.[6] Because the ships are all buried together and near a mortuary belonging to Pharaoh Khasekhemwy,[70] originally they were all thought to have belonged to him, but one of the 14 ships dates to 3000 BC,[70] and the associated pottery jars buried with the vessels also suggest earlier dating.[70] The ship dating to 3000 BC was 75 feet long[70] and is now thought to perhaps have belonged to an earlier pharaoh.[70] According to professor O'Connor, the 5,000-year-old ship may have even belonged to Pharaoh Aha.[70]

Early Egyptians also knew how to assemble planks of wood with treenails to fasten them together, using pitch for caulking the seams. The "Khufu ship", a 43.6-meter vessel sealed into a pit in the Giza pyramid complex at the foot of the Great Pyramid of Giza in the Fourth Dynasty around 2500 BC, is a full-size surviving example which may have fulfilled the symbolic function of a solar barque. Early Egyptians also knew how to fasten the planks of this ship together with mortise and tenon joints.[6] Despite the ancient Egyptian's ability to construct very large boats to sail along the easily navigable Nile, they were not known as good sailors and did not engage in widespread sailing or shipping in the Mediterranean or Red Seas.

Mathematics

The earliest attested examples of mathematical calculations date to the predynastic Naqada period, and show a fully developed number system.[71] The importance of mathematics to an educated Egyptian is suggested by a New Kingdom fictional letter in which the writer proposes a scholarly competition between himself and another scribe regarding everyday calculation tasks such as accounting of land, labor and grain.[72] Texts such as the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus and the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus show that the ancient Egyptians could perform the four basic mathematical operations — addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division — use fractions, compute the volumes of boxes and pyramids, and calculate the surface areas of rectangles, triangles, circles and even spheres[citation needed]. They understood basic concepts of algebra and geometry, and could solve simple sets of simultaneous equations.[73]

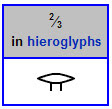

Mathematical notation was decimal, and based on hieroglyphic signs for each power of ten up to one million. Each of these could be written as many times as necessary to add up to the desired number; so to write the number eighty or eight hundred, the symbol for ten or one hundred was written eight times respectively.[74] Because their methods of calculation could not handle most fractions with a numerator greater than one, ancient Egyptian fractions had to be written as the sum of several fractions. For example, the fraction two-fifths was resolved into the sum of one-third + one-fifteenth; this was facilitated by standard tables of values.[75] Some common fractions, however, were written with a special glyph; the equivalent of the modern two-thirds is shown on the right.[76]

Ancient Egyptian mathematicians had a grasp of the principles underlying the Pythagorean theorem, knowing, for example, that a triangle had a right angle opposite the hypotenuse when its sides were in a 3–4–5 ratio.[77] They were able to estimate the area of a circle by subtracting one-ninth from its diameter and squaring the result:

Area ≈ [(8⁄9)D]2 = (256⁄81)r 2 ≈ 3.16r 2,

a reasonable approximation of the formula πr 2.[77][78]

The golden ratio seems to be reflected in many Egyptian constructions, including the pyramids, but its use may have been an unintended consequence of the ancient Egyptian practice of combining the use of knotted ropes with an intuitive sense of proportion and harmony.[79]

Legacy

The culture and monuments of ancient Egypt have left a lasting legacy on the world. The cult of the goddess Isis, for example, became popular in the Roman Empire, as obelisks and other relics were transported back to Rome.[80] The Romans also imported building materials from Egypt to erect structures in Egyptian style. Early historians such as Herodotus, Strabo and Diodorus Siculus studied and wrote about the land which became viewed as a place of mystery.[81] During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Egyptian pagan culture was in decline after the rise of Christianity and later Islam, but interest in Egyptian antiquity continued in the writings of medieval scholars such as Dhul-Nun al-Misri and al-Maqrizi.[82]

In the 17th and 18th centuries, European travelers and tourists brought back antiquities and wrote stories of their journeys, leading to a wave of Egyptomania across Europe. This renewed interest sent collectors to Egypt, who took, purchased, or were given many important antiquities.[83] Although the European colonial occupation of Egypt destroyed a significant portion of the country's historical legacy, some foreigners had more positive results. Napoleon, for example, arranged the first studies in Egyptology when he brought some 50 scientists and artists to study and document Egypt's natural history, which was published in the Description de l'Ėgypte.[84] In the 19th century, the Egyptian Government and archaeologists alike recognized the importance of cultural respect and integrity in excavations. The Supreme Council of Antiquities now approves and oversees all excavations, which are aimed at finding information rather than treasure. The council also supervises museums and monument reconstruction programs designed to preserve the historical legacy of Egypt.

Notes

1.Loprieno (1995b) p. 2137

2.Loprieno (2004) p. 161

3.Loprieno (2004) p. 162

4. Loprieno (1995b) p. 2137-38

5.Vittman (1991) pp. 197–227

6. Loprieno (1995a) p. 46

7. Loprieno (1995a) p. 74

8. Loprieno (2004) p. 175

9.Allen (2000) pp. 67, 70, 109

10. Loprieno (2005) p. 2147

11. Loprieno (2004) p. 173

12. Allen (2000) p. 13

13.Allen (2000) p. 7

14.Loprieno (2004) p. 166

15.El-Daly (2005) p. 164

16.Allen (2000) p. 8

17.Strouhal (1989) p. 235

18.Lichtheim (1975) p. 11

19.Lichtheim (1975) p. 215

20. "Wisdom in Ancient Israel", John Day,/John Adney Emerton,/Robert P. Gordon/ Hugh Godfrey/Maturin Williamson, p23, Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 0521624894

21. Lichtheim (1980) p. 159

22. Manuelian (1998) p. 401

23.Manuelian (1998) p. 403

24.Manuelian (1998) p. 405

25.Manuelian (1998) pp. 406–7

26.Manuelian (1998) pp. 399–400

27. "Music in Ancient Egypt". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/furniture/music.html. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

28. Manuelian (1998) p. 126

29. “The Cambridge Ancient History: II Part I , The Middle East and the Aegean Region, c.1800-13380 B.C”, Edited I.E.S Edwards–C.JGadd–N.G.L Hammond-E.Sollberger, Cambridge at the University Press, p. 380, 1973, ISBN 0-521-08230-7

30. Clarke (1990) pp. 94–7

31.Badawy (1968) p. 50

32."Types of temples in ancient Egypt". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/temple/typestime.html. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

33.Dodson (1991) p. 23

34.Robins (1997) p. 29

35.Robins (1997) p. 21

36.Robins (2001) p. 12

37.Nicholson (2000) p. 105

38.a b James (2005) p. 122

39.Robins (1998) p. 74

40.Shaw (2002) p. 216

41.Robins (1998) p. 149

42.Robins (1998) p. 158

43.James (2005) p. 102

44."The Oxford Guide: Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology", edited by Donald B. Redford, p. 106, Berkley, 2003, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

45.James (2005) p. 117

46.Shaw (2002) p. 313

47.Allen (2000) pp. 79, 94–5

48.Wasserman, et al. (1994) pp. 150–3

49."Mummies and Mummification: Old Kingdom". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/mummy/ok.html. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

50."Mummies and Mummification: Late Period, Ptolemaic, Roman and Christian Period". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/mummy/late.html. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

51."Shabtis". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/burialcustoms/shabtis.html. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

52.James (2005) p. 124

53.Shaw (2002) p. 245

54.Manuelian (1998) pp. 366–67

55.Clayton (1994) p. 96

56.Shaw (2002) p. 400

57.Nicholson (2000) p. 177

58.Nicholson (2000) p. 109

59.Nicholson (2000) p. 195

60.Nicholson (2000) p. 215

61.Filer (1995) p. 94

62.Filer (1995) pp. 78–80

63.Filer (1995) p. 21

64.Figures are given for adult life expectancy and do not reflect life expectancy at birth. Filer (1995) p. 25

65.Filer (1995) p. 39

66.Strouhal (1989) p. 243

67.Stroual (1989) pp. 244–46

68.Stroual (1989) p. 250

69.Filer (1995) p. 38

70.a b c d e f g Schuster, Angela M.H. "This Old Boat", December 11, 2000. Archaeological Institute of America.

71.Understanding of Egyptian mathematics is incomplete due to paucity of available material and lack of exhaustive study of the texts that have been uncovered. Imhausen et al. (2007) p. 13

72.Imhausen et al. (2007) p. 11

73. Clarke (1990) p. 222

74. Clarke (1990) p. 217

75. Clarke (1990) p. 218

76. Gardiner (1957) p. 197

77. a b Strouhal (1989) p. 241

78. Imhausen et al. (2007) p. 31

79. Kemp (1989) p. 138

80. Siliotti (1998) p. 8

81. Siliotti (1998) p. 10

82. El-Daly (2005) p. 112

83. Siliotti (1998) p. 13

84. Siliotti (1998) p. 100.

I recommend you that book to read ..See customer reviews below :-

The Egyptian language is a northern Afro-Asiatic language closely related to the Berber and Semitic languages.[1] It has the longest history of any language, having been written from c. 3200 BC to the Middle Ages and remaining as a spoken language for longer. The phases of Ancient Egyptian are Old Egyptian, Middle Egyptian (Classical Egyptian), Late Egyptian, Demotic and Coptic.[2] Egyptian writings do not show dialect differences before Coptic, but it was probably spoken in regional dialects around Memphis and later Thebes.[3]

Ancient Egyptian was a synthetic language, but it became more analytic later on. Late Egyptian develops prefixal definite and indefinite articles, which replace the older inflectional suffixes. There is a change from the older Verb Subject Object word order to Subject Verb Object.[4] The Egyptian hieroglyphic, hieratic, and demotic scripts were eventually replaced by the more phonetic Coptic alphabet. Coptic is still used in the liturgy of the Egyptian Orthodox Church, and traces of it are found in modern Egyptian Arabic.[5]

Sounds and grammar

Ancient Egyptian has 25 consonants similar to those of other Afro-Asiatic languages. These include pharyngeal and emphatic consonants, voiced and voiceless stops, voiceless fricatives and voiced and voiceless affricates. It has three long and three short vowels, which expanded in Later Egyptian to about nine.[6] The basic word in Egyptian, similar to Semitic and Berber, is a triliteral or biliteral root of consonants and semiconsonants. Suffixes are added to form words. The verb conjugation corresponds to the person. For example, the triconsonantal skeleton S-Ḏ-M is the semantic core of the word 'hear'; its basic conjugation is sḏm=f 'he hears'. If the subject is a noun, suffixes are not added to the verb:[7] sḏm ḥmt 'the woman hears'.

Adjectives are derived from nouns through a process that Egyptologists call nisbation because of its similarity with Arabic.[8] The word order is PREDICATE-SUBJECT in verbal and adjectival sentences, and SUBJECT-PREDICATE in nominal and adverbial sentences.[9] The subject can be moved to the beginning of sentences if it is long and is followed by a resumptive pronoun.[10] Verbs and nouns are negated by the particle n, but nn is used for adverbial and adjectival sentences. Stress falls on the ultimate or penultimate syllable, which can be open (CV) or closed (CVC).[11]

Writing

Hieroglyphic writing dates to c. 3200 BC, and is composed of some 500 symbols. A hieroglyph can represent a word, a sound, or a silent determinative; and the same symbol can serve different purposes in different contexts. Hieroglyphs were a formal script, used on stone monuments and in tombs, that could be as detailed as individual works of art. In day-to-day writing, scribes used a cursive form of writing, called hieratic, which was quicker and easier. While formal hieroglyphs may be read in rows or columns in either direction (though typically written from right to left), hieratic was always written from right to left, usually in horizontal rows. A new form of writing, Demotic, became the prevalent writing style, and it is this form of writing — along with formal hieroglyphs — that accompany the Greek text on the Rosetta Stone.[citation needed]

Around the 1st century AD, the Coptic alphabet started to be used alongside the Demotic script. Coptic is a modified Greek alphabet with the addition of some Demotic signs.[13] Although formal hieroglyphs were used in a ceremonial role until the 4th century AD, towards the end only a small handful of priests could still read them. As the traditional religious establishments were disbanded, knowledge of hieroglyphic writing was mostly lost. Attempts to decipher them date to the Byzantine[14] and Islamic periods in Egypt,[15] but only in 822, after the discovery of the Rosetta stone and years of research by Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion, were hieroglyphs almost fully deciphered.[16]

Literature

The Story of Sinuhe, written in Middle Egyptian, might be the classic of Egyptian literature.[18] Also written at this time was the Westcar Papyrus, a set of stories told to Khufu by his sons relating the marvels performed by priests.[19] The Instruction of Amenemope is considered a masterpiece of near-eastern literature.[20] Towards the end of the New Kingdom, the vernacular language was more often employed to write popular pieces like the Story of Wenamun and the Instruction of Any. The former tells the story of a noble who is robbed on his way to buy cedar from Lebanon and of his struggle to return to Egypt. From about 700 BC, narrative stories and instructions, such as the popular Instructions of Onchsheshonqy, as well as personal and business documents were written in the demotic script and phase of Egyptian. Many stories written in demotic during the Graeco-Roman period were set in previous historical eras, when Egypt was an independent nation ruled by great pharaohs such as Ramesses II.[21]

Culture

Daily life

Most ancient Egyptians were farmers tied to the land. Their dwellings were restricted to immediate family members, and were constructed of mud-brick designed to remain cool in the heat of the day. Each home had a kitchen with an open roof, which contained a grindstone for milling flour and a small oven for baking bread.[22] Walls were painted white and could be covered with dyed linen wall hangings. Floors were covered with reed mats, while wooden stools, beds raised from the floor and individual tables comprised the furniture.[23]

The ancient Egyptians placed a great value on hygiene and appearance. Most bathed in the Nile and used a pasty soap made from animal fat and chalk. Men shaved their entire bodies for cleanliness, and aromatic perfumes and ointments covered bad odors and soothed skin.[24] Clothing was made from simple linen sheets that were bleached white, and both men and women of the upper classes wore wigs, jewelry, and cosmetics. Children went without clothing until maturity, at about age 12, and at this age males were circumcised and had their heads shaved. Mothers were responsible for taking care of the children, while the father provided the family's income.[25]

The staple diet consisted of bread and beer, supplemented with vegetables such as onions and garlic, and fruit such as dates and figs. Wine and meat were enjoyed by all on feast days while the upper classes indulged on a more regular basis. Fish, meat, and fowl could be salted or dried, and could be cooked in stews or roasted on a grill.[26] Music and dance were popular entertainments for those who could afford them. Early instruments included flutes and harps, while instruments similar to trumpets, oboes, and pipes developed later and became popular. In the New Kingdom, the Egyptians played on bells, cymbals, tambourines, and drums and imported lutes and lyres from Asia.[27] The sistrum was a rattle-like musical instrument that was especially important in religious ceremonies.

The ancient Egyptians enjoyed a variety of leisure activities, including games and music. Senet, a board game where pieces moved according to random chance, was particularly popular from the earliest times; another similar game was mehen, which had a circular gaming board. Juggling and ball games were popular with children, and wrestling is also documented in a tomb at Beni Hasan.[28] The wealthy members of ancient Egyptian society enjoyed hunting and boating as well.

The excavation of the workers village of Deir el-Madinah has resulted in one of the most thoroughly documented accounts of community life in the ancient world that spans almost four hundred years. There is no comparable site in which the organisation, social interactions, working and living conditions of a community can be studied in such detail.[29]

Architecture

The architecture of ancient Egypt includes some of the most famous structures in the world: the Great Pyramids of Giza and the temples at Thebes. Building projects were organized and funded by the state for religious and commemorative purposes, but also to reinforce the power of the pharaoh. The ancient Egyptians were skilled builders; using simple but effective tools and sighting instruments, architects could build large stone structures with accuracy and precision.[30]

The domestic dwellings of elite and ordinary Egyptians alike were constructed from perishable materials such as mud bricks and wood, and have not survived. Peasants lived in simple homes, while the palaces of the elite were more elaborate structures. A few surviving New Kingdom palaces, such as those in Malkata and Amarna, show richly decorated walls and floors with scenes of people, birds, water pools, deities and geometric designs.[31] Important structures such as temples and tombs that were intended to last forever were constructed of stone instead of bricks. The architectural elements used in the world's first large-scale stone building, Djoser's mortuary complex, include post and lintel supports in the papyrus and lotus motif.

The earliest preserved ancient Egyptian temples, such as those at Giza, consist of single, enclosed halls with roof slabs supported by columns. In the New Kingdom, architects added the pylon, the open courtyard, and the enclosed hypostyle hall to the front of the temple's sanctuary, a style that was standard until the Graeco-Roman period.[32] The earliest and most popular tomb architecture in the Old Kingdom was the mastaba, a flat-roofed rectangular structure of mudbrick or stone built over an underground burial chamber. The step pyramid of Djoser is a series of stone mastabas stacked on top of each other. Pyramids were built during the Old and Middle Kingdoms, but later rulers abandoned them in favor of less conspicuous rock-cut tombs.[33]

Art

The ancient Egyptians produced art to serve functional purposes. For over 3500 years, artists adhered to artistic forms and iconography that were developed during the Old Kingdom, following a strict set of principles that resisted foreign influence and internal change.[34] These artistic standards — simple lines, shapes, and flat areas of color combined with the characteristic flat projection of figures with no indication of spatial depth — created a sense of order and balance within a composition. Images and text were intimately interwoven on tomb and temple walls, coffins, stelae, and even statues. The Narmer Palette, for example, displays figures which may also be read as hieroglyphs.[35] Because of the rigid rules that governed its highly stylized and symbolic appearance, ancient Egyptian art served its political and religious purposes with precision and clarity.[36]

Ancient Egyptian artisans used stone to carve statues and fine reliefs, but used wood as a cheap and easily carved substitute. Paints were obtained from minerals such as iron ores (red and yellow ochres), copper ores (blue and green), soot or charcoal (black), and limestone (white). Paints could be mixed with gum arabic as a binder and pressed into cakes, which could be moistened with water when needed.[37] Pharaohs used reliefs to record victories in battle, royal decrees, and religious scenes. Common citizens had access to pieces of funerary art, such as shabti statues and books of the dead, which they believed would protect them in the afterlife.[38] During the Middle Kingdom, wooden or clay models depicting scenes from everyday life became popular additions to the tomb. In an attempt to duplicate the activities of the living in the afterlife, these models show laborers, houses, boats, and even military formations that are scale representations of the ideal ancient Egyptian afterlife.[39]

Despite the homogeneity of ancient Egyptian art, the styles of particular times and places sometimes reflected changing cultural or political attitudes. After the invasion of the Hyksos in the Second Intermediate Period, Minoan-style frescoes were found in Avaris.[40] The most striking example of a politically driven change in artistic forms comes from the Amarna period, where figures were radically altered to conform to Akhenaten's revolutionary religious ideas.[41] This style, known as Amarna art, was quickly and thoroughly erased after Akhenaten's death and replaced by the traditional forms.[42]

Religious beliefs

Beliefs in the divine and in the afterlife were ingrained in ancient Egyptian civilization from its inception; pharaonic rule was based on the divine right of kings. The Egyptian pantheon was populated by gods who had supernatural powers and were called on for help or protection. However, the gods were not always viewed as benevolent, and Egyptians believed they had to be appeased with offerings and prayers. The structure of this pantheon changed continually as new deities were promoted in the hierarchy, but priests made no effort to organize the diverse and sometimes conflicting creation myths and stories into a coherent system.[43] These various conceptions of divinity were not considered contradictory but rather layers in the multiple facets of reality.[44]

Gods were worshiped in cult temples administered by priests acting on the king's behalf. At the center of the temple was the cult statue in a shrine. Temples were not places of public worship or congregation, and only on select feast days and celebrations was a shrine carrying the statue of the god brought out for public worship. Normally, the god's domain was sealed off from the outside world and was only accessible to temple officials. Common citizens could worship private statues in their homes, and amulets offered protection against the forces of chaos.[45] After the New Kingdom, the pharaoh's role as a spiritual intermediary was de-emphasized as religious customs shifted to direct worship of the gods. As a result, priests developed a system of oracles to communicate the will of the gods directly to the people.[46]

The Egyptians believed that every human being was composed of physical and spiritual parts or aspects. In addition to the body, each person had a šwt (shadow), a ba (personality or soul), a ka (life-force), and a name.[47] The heart, rather than the brain, was considered the seat of thoughts and emotions. After death, the spiritual aspects were released from the body and could move at will, but they required the physical remains (or a substitute, such as a statue) as a permanent home. The ultimate goal of the deceased was to rejoin his ka and ba and become one of the "blessed dead", living on as an akh, or "effective one". In order for this to happen, the deceased had to be judged worthy in a trial, in which the heart was weighed against a "feather of truth". If deemed worthy, the deceased could continue their existence on earth in spiritual form.[48]

Burial customs

The ancient Egyptians maintained an elaborate set of burial customs that they believed were necessary to ensure immortality after death. These customs involved preserving the body by mummification, performing burial ceremonies, and interring, along with the body, goods to be used by the deceased in the afterlife.[38] Before the Old Kingdom, bodies buried in desert pits were naturally preserved by desiccation. The arid, desert conditions continued to be a boon throughout the history of ancient Egypt for the burials of the poor, who could not afford the elaborate burial preparations available to the elite. Wealthier Egyptians began to bury their dead in stone tombs and, as a result, they made use of artificial mummification, which involved removing the internal organs, wrapping the body in linen, and burying it in a rectangular stone sarcophagus or wooden coffin. Beginning in the Fourth Dynasty, some parts were preserved separately in canopic jars.[49]

By the New Kingdom, the ancient Egyptians had perfected the art of mummification; the best technique took 70 days and involved removing the internal organs, removing the brain through the nose, and desiccating the body in a mixture of salts called natron. The body was then wrapped in linen with protective amulets inserted between layers and placed in a decorated anthropoid coffin. Mummies of the Late Period were also placed in painted cartonnage mummy cases. Actual preservation practices declined during the Ptolemaic and Roman eras, while greater emphasis was placed on the outer appearance of the mummy, which was decorated.[50]

Wealthy Egyptians were buried with larger quantities of luxury items, but all burials, regardless of social status, included goods for the deceased. Beginning in the New Kingdom, books of the dead were included in the grave, along with shabti statues that were believed to perform manual labor for them in the afterlife.[51] Rituals in which the deceased was magically re-animated accompanied burials. After burial, living relatives were expected to occasionally bring food to the tomb and recite prayers on behalf of the deceased.[52]

Military

The ancient Egyptian military was responsible for defending Egypt against foreign invasion, and for maintaining Egypt's domination in the ancient Near East. The military protected mining expeditions to the Sinai during the Old Kingdom and fought civil wars during the First and Second Intermediate Periods. The military was responsible for maintaining fortifications along important trade routes, such as those found at the city of Buhen on the way to Nubia. Forts also were constructed to serve as military bases, such as the fortress at Sile, which was a base of operations for expeditions to the Levant. In the New Kingdom, a series of pharaohs used the standing Egyptian army to attack and conquer Kush and parts of the Levant.[53]

Typical military equipment included bows and arrows, spears, and round-topped shields made by stretching animal skin over a wooden frame. In the New Kingdom, the military began using chariots that had earlier been introduced by the Hyksos invaders. Weapons and armor continued to improve after the adoption of bronze: shields were now made from solid wood with a bronze buckle, spears were tipped with a bronze point, and the Khopesh was adopted from Asiatic soldiers.[54] The pharaoh was usually depicted in art and literature riding at the head of the army, and there is evidence that at least a few pharaohs, such as Seqenenre Tao II and his sons, did do so.[55] Soldiers were recruited from the general population, but during, and especially after, the New Kingdom, mercenaries from Nubia, Kush, and Libya were hired to fight for Egypt.[56]

Technology, medicine, and mathematics

Technology

In technology, medicine and mathematics, ancient Egypt achieved a relatively high standard of productivity and sophistication. Traditional empiricism, as evidenced by the Edwin Smith and Ebers papyri (c. 600 BC), is first credited to Egypt, and the roots of the scientific method can also be traced back to the ancient Egyptians.[citation needed] The Egyptians created their own alphabet and decimal system.

Faience and glass

Even before the Old Kingdom, the ancient Egyptians had developed a glassy material known as faience, which they treated as a type of artificial semi-precious stone. Faience is a non-clay ceramic made of silica, small amounts of lime and soda, and a colorant, typically copper.[57] The material was used to make beads, tiles, figurines, and small wares. Several methods can be used to create faience, but typically production involved application of the powdered materials in the form of a paste over a clay core, which was then fired. By a related technique, the ancient Egyptians produced a pigment known as Egyptian Blue, also called blue frit, which is produced by fusing (or sintering) silica, copper, lime, and an alkali such as natron. The product can be ground up and used as a pigment.[58]

The ancient Egyptians could fabricate a wide variety of objects from glass with great skill, but it is not clear whether they developed the process independently.[59] It is also unclear whether they made their own raw glass or merely imported pre-made ingots, which they melted and finished. However, they did have technical expertise in making objects, as well as adding trace elements to control the color of the finished glass. A range of colors could be produced, including yellow, red, green, blue, purple, and white, and the glass could be made either transparent or opaque.[60]

Medicine

The medical problems of the ancient Egyptians stemmed directly from their environment. Living and working close to the Nile brought hazards from malaria and debilitating schistosomiasis parasites, which caused liver and intestinal damage. Dangerous wildlife such as crocodiles and hippos were also a common threat. The life-long labors of farming and building put stress on the spine and joints, and traumatic injuries from construction and warfare all took a significant toll on the body. The grit and sand from stone-ground flour abraded teeth, leaving them susceptible to abscesses (though caries were rare).[61]

The diets of the wealthy were rich in sugars, which promoted periodontal disease.[62] Despite the flattering physiques portrayed on tomb walls, the overweight mummies of many of the upper class show the effects of a life of overindulgence.[63] Adult life expectancy was about 35 for men and 30 for women, but reaching adulthood was difficult as about one-third of the population died in infancy.[64]

Ancient Egyptian physicians were renowned in the ancient Near East for their healing skills, and some, like Imhotep, remained famous long after their deaths.[65] Herodotus remarked that there was a high degree of specialization among Egyptian physicians, with some treating only the head or the stomach, while others were eye-doctors and dentists.[66] Training of physicians took place at the Per Ankh or "House of Life" institution, most notably those headquartered in Per-Bastet during the New Kingdom and at Abydos and Saïs in the Late period. Medical papyri show empirical knowledge of anatomy, injuries, and practical treatments.[67]

Wounds were treated by bandaging with raw meat, white linen, sutures, nets, pads and swabs soaked with honey to prevent infection,[68] while opium was used to relieve pain. Garlic and onions were used regularly to promote good health and were thought to relieve asthma symptoms. Ancient Egyptian surgeons stitched wounds, set broken bones, and amputated diseased limbs, but they recognized that some injuries were so serious that they could only make the patient comfortable until he died.[69]

Shipbuilding

Early Egyptians knew how to assemble planks of wood into a ship hull as early as 3000 BC. The Archaeological Institute of America reports[6] that the oldest ships yet unearthed, a group of 14 discovered in Abydos, were constructed of wooden planks which were "sewn" together. Discovered by Egyptologist David O'Connor of New York University,[70] woven straps were found to have been used to lash the planks together,[6] and reeds or grass stuffed between the planks helped to seal the seams.[6] Because the ships are all buried together and near a mortuary belonging to Pharaoh Khasekhemwy,[70] originally they were all thought to have belonged to him, but one of the 14 ships dates to 3000 BC,[70] and the associated pottery jars buried with the vessels also suggest earlier dating.[70] The ship dating to 3000 BC was 75 feet long[70] and is now thought to perhaps have belonged to an earlier pharaoh.[70] According to professor O'Connor, the 5,000-year-old ship may have even belonged to Pharaoh Aha.[70]

Early Egyptians also knew how to assemble planks of wood with treenails to fasten them together, using pitch for caulking the seams. The "Khufu ship", a 43.6-meter vessel sealed into a pit in the Giza pyramid complex at the foot of the Great Pyramid of Giza in the Fourth Dynasty around 2500 BC, is a full-size surviving example which may have fulfilled the symbolic function of a solar barque. Early Egyptians also knew how to fasten the planks of this ship together with mortise and tenon joints.[6] Despite the ancient Egyptian's ability to construct very large boats to sail along the easily navigable Nile, they were not known as good sailors and did not engage in widespread sailing or shipping in the Mediterranean or Red Seas.

Mathematics

The earliest attested examples of mathematical calculations date to the predynastic Naqada period, and show a fully developed number system.[71] The importance of mathematics to an educated Egyptian is suggested by a New Kingdom fictional letter in which the writer proposes a scholarly competition between himself and another scribe regarding everyday calculation tasks such as accounting of land, labor and grain.[72] Texts such as the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus and the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus show that the ancient Egyptians could perform the four basic mathematical operations — addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division — use fractions, compute the volumes of boxes and pyramids, and calculate the surface areas of rectangles, triangles, circles and even spheres[citation needed]. They understood basic concepts of algebra and geometry, and could solve simple sets of simultaneous equations.[73]

Mathematical notation was decimal, and based on hieroglyphic signs for each power of ten up to one million. Each of these could be written as many times as necessary to add up to the desired number; so to write the number eighty or eight hundred, the symbol for ten or one hundred was written eight times respectively.[74] Because their methods of calculation could not handle most fractions with a numerator greater than one, ancient Egyptian fractions had to be written as the sum of several fractions. For example, the fraction two-fifths was resolved into the sum of one-third + one-fifteenth; this was facilitated by standard tables of values.[75] Some common fractions, however, were written with a special glyph; the equivalent of the modern two-thirds is shown on the right.[76]

Ancient Egyptian mathematicians had a grasp of the principles underlying the Pythagorean theorem, knowing, for example, that a triangle had a right angle opposite the hypotenuse when its sides were in a 3–4–5 ratio.[77] They were able to estimate the area of a circle by subtracting one-ninth from its diameter and squaring the result:

Area ≈ [(8⁄9)D]2 = (256⁄81)r 2 ≈ 3.16r 2,

a reasonable approximation of the formula πr 2.[77][78]

The golden ratio seems to be reflected in many Egyptian constructions, including the pyramids, but its use may have been an unintended consequence of the ancient Egyptian practice of combining the use of knotted ropes with an intuitive sense of proportion and harmony.[79]

Legacy

The culture and monuments of ancient Egypt have left a lasting legacy on the world. The cult of the goddess Isis, for example, became popular in the Roman Empire, as obelisks and other relics were transported back to Rome.[80] The Romans also imported building materials from Egypt to erect structures in Egyptian style. Early historians such as Herodotus, Strabo and Diodorus Siculus studied and wrote about the land which became viewed as a place of mystery.[81] During the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Egyptian pagan culture was in decline after the rise of Christianity and later Islam, but interest in Egyptian antiquity continued in the writings of medieval scholars such as Dhul-Nun al-Misri and al-Maqrizi.[82]

In the 17th and 18th centuries, European travelers and tourists brought back antiquities and wrote stories of their journeys, leading to a wave of Egyptomania across Europe. This renewed interest sent collectors to Egypt, who took, purchased, or were given many important antiquities.[83] Although the European colonial occupation of Egypt destroyed a significant portion of the country's historical legacy, some foreigners had more positive results. Napoleon, for example, arranged the first studies in Egyptology when he brought some 50 scientists and artists to study and document Egypt's natural history, which was published in the Description de l'Ėgypte.[84] In the 19th century, the Egyptian Government and archaeologists alike recognized the importance of cultural respect and integrity in excavations. The Supreme Council of Antiquities now approves and oversees all excavations, which are aimed at finding information rather than treasure. The council also supervises museums and monument reconstruction programs designed to preserve the historical legacy of Egypt.

Notes

1.Loprieno (1995b) p. 2137

2.Loprieno (2004) p. 161

3.Loprieno (2004) p. 162

4. Loprieno (1995b) p. 2137-38

5.Vittman (1991) pp. 197–227

6. Loprieno (1995a) p. 46

7. Loprieno (1995a) p. 74

8. Loprieno (2004) p. 175

9.Allen (2000) pp. 67, 70, 109

10. Loprieno (2005) p. 2147

11. Loprieno (2004) p. 173

12. Allen (2000) p. 13

13.Allen (2000) p. 7

14.Loprieno (2004) p. 166

15.El-Daly (2005) p. 164

16.Allen (2000) p. 8

17.Strouhal (1989) p. 235

18.Lichtheim (1975) p. 11

19.Lichtheim (1975) p. 215

20. "Wisdom in Ancient Israel", John Day,/John Adney Emerton,/Robert P. Gordon/ Hugh Godfrey/Maturin Williamson, p23, Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 0521624894

21. Lichtheim (1980) p. 159

22. Manuelian (1998) p. 401

23.Manuelian (1998) p. 403

24.Manuelian (1998) p. 405

25.Manuelian (1998) pp. 406–7

26.Manuelian (1998) pp. 399–400

27. "Music in Ancient Egypt". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/furniture/music.html. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

28. Manuelian (1998) p. 126

29. “The Cambridge Ancient History: II Part I , The Middle East and the Aegean Region, c.1800-13380 B.C”, Edited I.E.S Edwards–C.JGadd–N.G.L Hammond-E.Sollberger, Cambridge at the University Press, p. 380, 1973, ISBN 0-521-08230-7

30. Clarke (1990) pp. 94–7

31.Badawy (1968) p. 50

32."Types of temples in ancient Egypt". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/temple/typestime.html. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

33.Dodson (1991) p. 23

34.Robins (1997) p. 29

35.Robins (1997) p. 21

36.Robins (2001) p. 12

37.Nicholson (2000) p. 105

38.a b James (2005) p. 122

39.Robins (1998) p. 74

40.Shaw (2002) p. 216

41.Robins (1998) p. 149

42.Robins (1998) p. 158

43.James (2005) p. 102

44."The Oxford Guide: Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology", edited by Donald B. Redford, p. 106, Berkley, 2003, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

45.James (2005) p. 117

46.Shaw (2002) p. 313

47.Allen (2000) pp. 79, 94–5

48.Wasserman, et al. (1994) pp. 150–3

49."Mummies and Mummification: Old Kingdom". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/mummy/ok.html. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

50."Mummies and Mummification: Late Period, Ptolemaic, Roman and Christian Period". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/mummy/late.html. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

51."Shabtis". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/burialcustoms/shabtis.html. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

52.James (2005) p. 124

53.Shaw (2002) p. 245

54.Manuelian (1998) pp. 366–67

55.Clayton (1994) p. 96

56.Shaw (2002) p. 400

57.Nicholson (2000) p. 177

58.Nicholson (2000) p. 109

59.Nicholson (2000) p. 195

60.Nicholson (2000) p. 215

61.Filer (1995) p. 94

62.Filer (1995) pp. 78–80

63.Filer (1995) p. 21

64.Figures are given for adult life expectancy and do not reflect life expectancy at birth. Filer (1995) p. 25

65.Filer (1995) p. 39

66.Strouhal (1989) p. 243

67.Stroual (1989) pp. 244–46

68.Stroual (1989) p. 250

69.Filer (1995) p. 38

70.a b c d e f g Schuster, Angela M.H. "This Old Boat", December 11, 2000. Archaeological Institute of America.

71.Understanding of Egyptian mathematics is incomplete due to paucity of available material and lack of exhaustive study of the texts that have been uncovered. Imhausen et al. (2007) p. 13

72.Imhausen et al. (2007) p. 11

73. Clarke (1990) p. 222

74. Clarke (1990) p. 217

75. Clarke (1990) p. 218

76. Gardiner (1957) p. 197

77. a b Strouhal (1989) p. 241

78. Imhausen et al. (2007) p. 31

79. Kemp (1989) p. 138

80. Siliotti (1998) p. 8

81. Siliotti (1998) p. 10

82. El-Daly (2005) p. 112

83. Siliotti (1998) p. 13

84. Siliotti (1998) p. 100.

I recommend you that book to read ..See customer reviews below :-

Labels:

and mathematics,

Architecture,

Art,

Culture,

Daily life,

Egypt Military,

Language of Ancient Egypt,

Literature,

medicine,

Religious beliefsBurial customs,

Sounds and grammar,

Technology,

Writing

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment